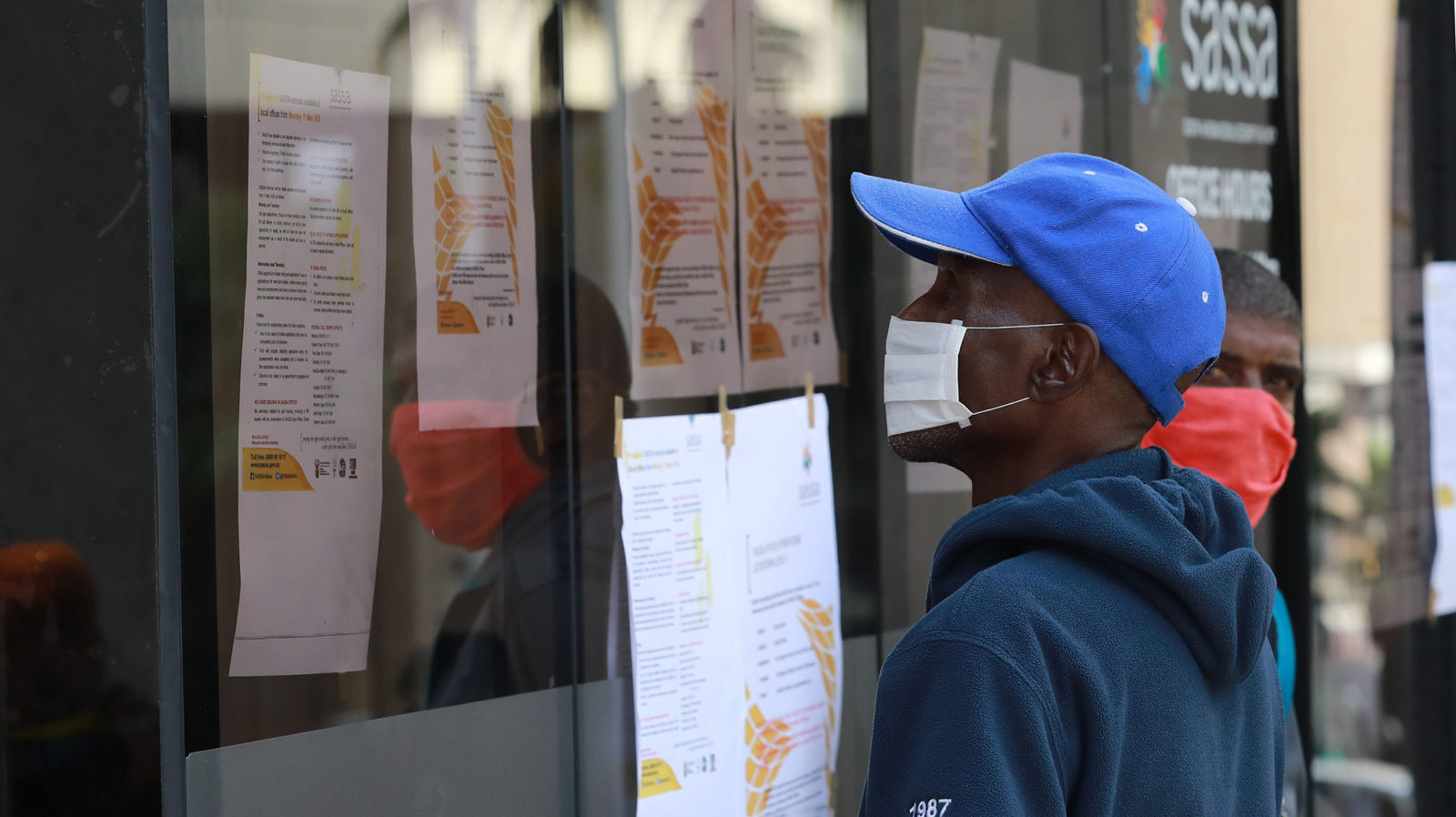

About 17 million South Africans rely on social grants for their household income and food security. So how have the twin components of social distancing and economic relief measures been experienced by poor South Africans dependent on social grants?

The South African government has been lauded for its decisive intervention to implement a lockdown and physical distancing to mitigate the impact of Covid-19 on the healthcare system. The ensuing tension between combatting a health crisis and precipitating an economic collapse has been the subject of much public comment – about the economy, about small business and about employment.

The government has also received accolades for heeding the call from civil society, academics and communities to provide social and economic relief measures to mitigate the impact of the lockdowns. These measures included underwriting bank loans from commercial banks to businesses, rejigging the 2020 budget to shift money to healthcare and to the provinces, increasing social grants and providing food vouchers and packages.

Prior to the lockdown, some 17 million South Africans were relying on social grants for their household income and food security. So how have the twin components of social distancing and economic relief measures worked for poor South Africans dependent on social grants?

Since 2015, the health systems unit of the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC), has been conducting a mixed-methods study exploring the impact of the child support grant (CSG) on child nutritional status and recipients’ experience of utilising the CSG to access food for child beneficiaries under five in Langa outside Cape Town. As part of the qualitative component of the study, in-depth interviews were conducted with primary recipients and non-recipient primary caregivers.

Preliminary findings from this ongoing study show that we may be experiencing the worst of both worlds – both a failure of the lockdown to achieve physical distancing in the poorest areas, and a devastating impact on food security and household income.

Some people are afraid to go to the clinic for fear of being infected with Covid-19, or of being harassed by the police on the way to or from health facilities. This has important implications for the management of chronic illnesses and the provision of preventive healthcare services during Covid-19.

The news of the increase in social grants has been welcomed in many households, but concerns about the continued impact of the pandemic on the ability of caregivers to provide food for their children and households remain. The study’s findings raise some important points that need to be taken into consideration by the government, as the virus continues to spread and lockdown restrictions remain in place.

Lockdown is possible for those living in formal areas as they have yards, even if small, for children to play in. However, lockdown is ‘impossible’ for those living in informal settlements.

In informal settlements, families live in small shacks crammed together with little outside area for children to play in. Children are thus forced to play in the streets and parks, and parents live in constant fear of their children contracting Covid-19 and bringing it home.

Access to water and sanitation is on a communal basis and facilities are often some distance from the shacks.

Communities experience frequent power cuts which necessitate street committee meetings with people standing next to each other, and frequent trips to shops to buy paraffin. Community members are sometimes harassed by the police when out getting provisions or visiting the clinic.

In one household, a 35-year-old mother of three living in an informal settlement spoke of her fear for her children when they go outside to play. Even so, she does not stop them as she feels it would be unfair to keep them inside her one-room shack all day.

According to participants, the one positive outcome of the lockdown is that crime is down. They mainly attribute this to the prohibition of the sale of alcohol and, to a lesser extent, an increased police presence.

Meanwhile, some of the government’s announcements on grants are confusing recipients. The CSG, with an increase, was initially understood to be R400, but was subsequently reported to be R300, with some outlets now reporting it to be R350. In the initial announcement, it was generally understood that the CSG increase of R500 from June would continue to be per child. However, subsequent briefings announced that the increase would only be per caregiver from the month of June. The participants we have interviewed continue to believe that the increase will be per child, and are not aware that the increase of the CSG enjoyed in May will effectively end and be replaced by a caregiver component in June. Considering the already low value of the grant, a difference in what is expected and what is actually received can have a major impact on household food security.

Primary caregivers welcome the top-up as a step in the right direction, but believe the increase to be inadequate. Caregivers report a number of outcomes that demonstrate this inadequacy. Among these are:

- Increased food needs as a result of children being housebound;

- Loss of non-grant income in some households;

- Households with only one or two CSGs as the main source of income;

- Primary caregivers of children receiving the CSG being ineligible for the Social Relief of Distress Grant (SROD);

- Loss of school meals for children who received this service when schools were open;

- People being unable to rely on their usual reciprocity networks for borrowing money and food; and

- Food price increases.

In one household with a family of four (a mother, father and two children), the father worked as a casual labourer for a textile factory. As a result of the lockdown, he lost his job and does not qualify for UIF. The family went from relying on his income plus two CSGs, to having the two grants as the only source of income. His unemployed wife is unable to claim for the SROD because she is already a recipient of the CSG on behalf of her children. Thus, based on the two CSGs, the total monthly income for this family will likely be about R1,380 from June, a decrease of R100 from the previous month.

Caregivers interviewed suggested that CSG recipients should be further supported with regular and reliable non-cash assistance in the form of food vouchers and/or food parcels. None of the participants in the study had received food parcels from government.

Although small food parcels have been received by some primary caregivers from NGOS and from children attending ECD centres, community members are unclear about the eligibility criteria and the procedure for receiving SASSA food parcels.

Access to routine healthcare services during lockdown is difficult for individuals with chronic illnesses and those needing family planning and vaccinations for children.

Participants have reported that clinics are only allowing the collection of chronic medications and are not providing GP or routine check-up services “unless you are seriously ill”.

Some people are afraid to go to the clinic for fear of being infected with Covid-19, or of being harassed by the police on the way to or from health facilities. This has important implications for the management of chronic illnesses and the provision of preventive healthcare services during Covid-19.

It is going to take more than a small increase in social grants – however welcome they are – to mitigate the short and long-term impacts of Covid-19 on poor households, with and without children.

If government is serious about the poor receiving social grants, it is going to take a multi-sectoral response that ensures an increase in cash and non-cash resources to poor households and children; continuity of access to routine healthcare services so that the flattening of the curve is not at the expense of gains made in survival of children through preventive health services including immunisation; and improved access to basic services, including adequate shelter, water and sanitation services. DM

Doctors Wanga Zembe-Mkabile, Vundli Ramokolo and Tanya Doherty are researchers in the Health Systems Research Unit of the SA Medical Research Council.

Original article published in the Maverick Citizen