With nearly 20,000 perinatal deaths in South Africa each year, a locally developed low-cost device has been shown to reduce deaths by 40%, inspiring hope.

As we are clearly seeing with the COVID-19 crisis, the development of new tools and diagnostics is central to fighting disease, including for maternal and child health. The South African government plays a critical role in funding research and development to solve local health challenges and has committed to allocating 0.15% of GDP on health research. This funding, which is currently at 0.003% of GDP, is essential to meeting our country’s urgent health needs while also building research infrastructure and manufacturing capacities that strengthen South Africa’s regional leadership and yield economic return.

Researchers and innovators across South Africa are always working to develop lifesaving tools. One example of this is the collaboration between the Department of Science and Innovation, researchers from the South Africa’s Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, and the South African Medical Research Council in the development of a low-cost Doppler ultrasound called the Umbiflow™ to improve care for pregnant women and their babies.

The Umbiflow™ is used for screening expectant mothers, helping prevent complications during pregnancy and childbirth through early identification of those at higher risk. The low-cost Doppler ultrasound ensures that the technology needed for early identification of high-risk pregnancies is available and accessible to more health care workers in PHC settings. This innovation is easy to learn how to use and does not require highly trained health professionals, allowing for wider use and improved access—reducing the number of pregnant women being referred to secondary health care facilities.

“There is no doubt in our population in South Africa that it would be worth screening the population, and we would save a lot of lives. And if we do some rough estimates, if we screen 95% of pregnant women in the third trimester, we could save or prevent around 4,000 stillbirths a year,” said Emeritus Professor Robert Pattinson, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at the University of Pretoria.

A healthcare worker using Umbiflow™ in a clinic. Photo Credit: Tsakane Hlongwane.

While Doppler ultrasound technology has several important applications in health care, one of the main historical barriers to its widespread use is cost. In many developing nations, health care facilities simply cannot afford Doppler ultrasound equipment, leaving patients—and especially pregnant women—with less-than-optimal quality of care. Another barrier is the need for a trained sonographer to be at the clinic in order to use the ultrasound equipment and interpret the results. Umbiflow™ makes this technology available at a low cost and in a form that is easy to use, opening the door for more health care workers to use the technology.

What is Umbiflow™?

Umbiflow™ is a sophisticated portable device that estimates the flow of blood in the umbilical cord, which allows health care practitioners to ensure sufficient supply of oxygen and nutrition to a growing fetus. The measurement is used to recommend specialist intervention, should the fetus be at risk.

Field trials conducted between 2002-2004 in Kraaifontein in the Western Cape of South Africa showed that referrals of patients with suspected fetal growth restriction can be reduced by 55% if the Umbiflow™ technology is made available at the primary care level. Using Umbiflow™ at a clinic was shown to be more cost-effective than referral to a secondary hospital for a Doppler test.

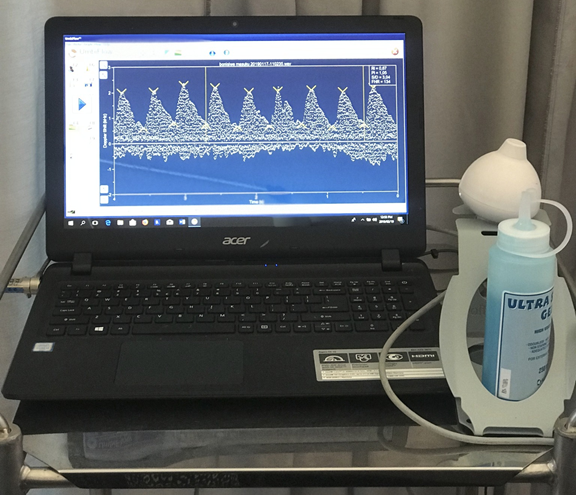

“Umbiflow™ was specifically designed for use by nursing staff and midwives at primary health care facilities and antenatal clinics in remote and low-resource settings. It consists of a self-contained software programme and a hand-held probe that plugs into the USB port of a computer (desktop, notebook or tablet). The USB port provides power to the probe and facilitates the signal transfer to a software application.

The software processes the ultrasound signals to generate a high-quality depiction of the umbilical blood flow, and automatically calculates the so-called “resistance index” (RI) which can be directly linked to the functioning of the placenta. The blood flow in the umbilical cord is also audible in the loudspeakers and a digital interface allows the user to print the test results” says Jeremy Wallis of the Industrial Sensors Impact Area at CSIR.

The Umbiflow™ is connected to the mobile network, allowing for remote expert monitoring so that centrally located obstetricians can provide support to nurses in the field in real-time, if required.

A typical Umbiflow™ Doppler measurement showing umbilical blood flow against time (4 seconds of data). Photo credit: CSIR.

The telemedicine aspect of this technology provides additional benefits of quality assurance, system surveillance, and electronic health record management.

“Umbiflow makes it possible to perform umbilical blood flow assessments at primary health care clinics and this enables the separation of actual high-risk pregnancies from the clinically-determined high-risk pregnancies, with a 90% reduction in referral rates to specialist care centers,” adds Professor Tony Bunn, the former Director of the Innovation Centre at SAMRC.

The development of the Umbiflow™ dates to the late 1980s at Tygerberg Academic Hospital (TAH) when Prof Hein Odendaal, Emeritus Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Stellenbosch University, suggested the development of a suitable ultrasound device. Over the past three decades, the innovation has transformed from a tool for confirming the association between abnormal placental blood flow and poor perinatal outcomes in 50 patients to the subject of multi-country clinical studies.

Development of the Umbiflow™ was funded by the South African Department of Science and Innovation, through the National Research Foundation’s Innovation Fund, CSIR, and the SAMRC. A first prototype was tested in clinics and Tygerberg Hospital in the Western Cape. The tests demonstrated that the Umbiflow™ device could accurately measure the Resistance Index (RI) of the umbilical blood flow and provide suitable data to guide referral decisions at low cost. Testing also demonstrated that the technology could be successfully operated by midwives at antenatal clinics.

Umbiflow™ – a game-changer

According to Dr. Tsakane Hlongwane—a gynecology and obstetrics specialist with the University of Pretoria who has been involved in nine site trials of Umbiflow™ since 2017—most antenatal clinics in South Africa do not have a tool or device to detect at-risk babies during pregnancy.

“Currently one of the ways to determine the fetal growth rate at the primary care level in South Africa and in countries in Sub Saharan Africa is by measuring the symphysis-fundal height manually, by use of a technique involving a tape measure to determine the distance across the mother’s abdomen from the pubic bone to the top of the uterus,” says Dr Tsakane.

In clinics where ultrasound machines are not available, measurement is done by tape measure and plotted against a fetal growth chart. However, misdiagnosis with this approach is common. If misdiagnosed, the patient incurs extra costs related to transport, time, and lost income whilst seeking health care in a secondary-level institution. Furthermore, the secondary-level health system is usually strained, and affordable ultrasound technology can help ensure appropriate diagnosis at the first point of care and prevent these burdens on patients and health systems.

“One could say, the symphysis height is 35 and someone else would say something else. So, it’s very subjective, and most of the literature says that it’s not reliable. This is where the Umbiflow™ comes in,” adds Dr. Tsakane.

Dr. Valerie Vannevel, a researcher at SAMRC and the clinical lead for Umbiflow™ in Ghana, Kenya, Rwanda, and India where studies are currently taking place, says the aim of the Umbiflow™ is to find babies who are at risk of not growing properly during pregnancies. It can identify problems with the placenta which would increase the risk of a stillbirth.

“We have a lot of stillbirths in South Africa—more than we have early neonatal deaths (babies who are born alive but die within 7 days after birth), which is not really the same in other places in the world. It is something that is very prevalent in our context. And obviously with stillbirths you can sometimes explain why it happened if the woman is at risk of complications—for instance, if she has high blood pressure and has what we call a high-risk pregnancy. However, we do find a lot of stillbirths to women who we really classify as a low-risk woman: a woman who is healthy, who previously maybe had normal pregnancies, healthy babies but she ends up having a stillbirth”.

“Conventional Doppler ultrasound units are beyond the reach of the majority of primary care facilities in the country, as only specialists can operate them. With a large rural or semi-rural population and large numbers of people living at low-income levels in South Africa, the device is really in essence revolutionary,” says Prof Pattinson, who led the clinical studies of Umbiflow™ in Tshwane, Mamelodi. Women in those areas have access to this test.

Umbiflow™ would help South Africa make progress toward Sustainable Development Goal 3 around mother and child health. Additionally, it reinforces WHO guidelines by improving quality of antenatal care to reduce the risk of stillbirths and pregnancy complications. It also addresses three of the four priorities of the South African National Department of Health; namely, increasing life expectancy, decreasing mother and child mortality, and strengthening the health system effectiveness.

The new, lower-cost devices are expected to help South Africa’s Department of Health meet its priorities to decrease child mortality (South Africa is 164th out of 220 countries); and improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the health care system. The Umbiflow™ device has been tested widely on thousands of patients, and the results show Umbiflow™ is just as accurate as conventional, more expensive Doppler ultrasound equipment.

Through improved access to the Doppler measurement, Umbiflow™ can reduce the perinatal mortality rate. Literature suggests Doppler ultrasound equipment used in combination with set clinical management protocols can reduce the mortality rate of babies in high-risk pregnancies by 38 percent on average, when compared to a health care system that does not use Doppler ultrasound. Use of the Umbiflow™ has now shown that screening with Doppler ultrasound in low-risk pregnancies is also very beneficial in South Africa.

“There has been concern not just only with the clinicians, but the midwives worrying if they would be able to screen and use the device itself. But what has been great is that at our antenatal clinics, when we screen a patient, the people who are actually doing the screening are the midwives and nursing staff. The Umbiflow™ device is a fast learning curve with regards to using the Doppler itself,” says Dr. Tsakane.

She adds that a “majority of the midwives that we have worked with were able to master the use of the Doppler, the interpretation and getting to work with patients all within two weeks.”

Through connectivity, Umbiflow™ will furthermore be able to provide accurate and up-to-date statistics on medical conditions being assessed at the point of care (primary level), and on the quality of data measurements being done by staff at this level.

For her part, Dr. Vannevel indicates that in South Africa, “it looks like the device would be really beneficial. We can scale it up and it would be part of the BANC protocol, the normal Basic Antenatal Care. It can be done by the nurse, to midwife, to doctor, and you don’t need an experienced ultrasound person to do this. Anyone can do it and the results are fairly easy to interpret.”

So, what next?

Umbiflow™ is an example of how locally-driven innovation can better meet the needs of communities, improve standards of living, and drive progress toward achieving the SDGs. As COVID-19 has shown us, we will need new innovations and new tools. Innovations like this highlight the need for continued investments and commitments for health research and development.

Prof. Tony Bunn, former Director of the Innovation Centre of the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC), urges that developing countries need affordable and accessible health technologies in order to achieve better primary health care services. “It’s absurd that of the $70 billion spent on health research and development annually, only 10% is used to research 90% of the world’s health problems,” he says.

“WHO has provided funding for an international study and we are running prevalence studies in five countries, namely Ghana, Rwanda, Kenya, India, and South Africa. The study has just been completed and the data is being analyzed, and we hope to see a reflection of the prevalence of abnormal resistance indices in low-income countries,” says Prof Pattinson.

“We are currently doing follow up studies to see what it takes to scale up the implementation of Umbiflow™. We plan to introduce it over time in 87 clinics in Tshwane, Gauteng, which does about 50,000 deliveries a year. Unfortunately, the study is being delayed because of the COVID-19 pandemic,” adds Prof Pattinson.

Dr Vannevel notes that adopting a policy that drives wider implementation of the Umbiflow™ would be the first step to reducing the high rate of perinatal deaths in developing countries. DM

This article was written by Dr Tsakane Hlongwane, Sibusiso Hlatjwako, Taonga Chilalika, Douglas Waudo, Prof. Robert Pattinson, Prof. Hein Odendaal, Jeremy Wallis, Dr Tony Bunn, Dr Michelle Mulder and Dr Valerie Vannevel

Original article available on the Daily Maverick's website